Around the world, tens of thousands of researchers are in painstaking pursuit of new treatments that will conquer cancer. Few of them may ever know first-hand what it’s like to fight the disease, a leading cause of death that accounts for one in six deaths worldwide. Jan Rosenbaum ’78, who spent much of her career as a cancer fighter, recently found herself in the position of blood cancer patient — an experience, she says, that helped inform her work.

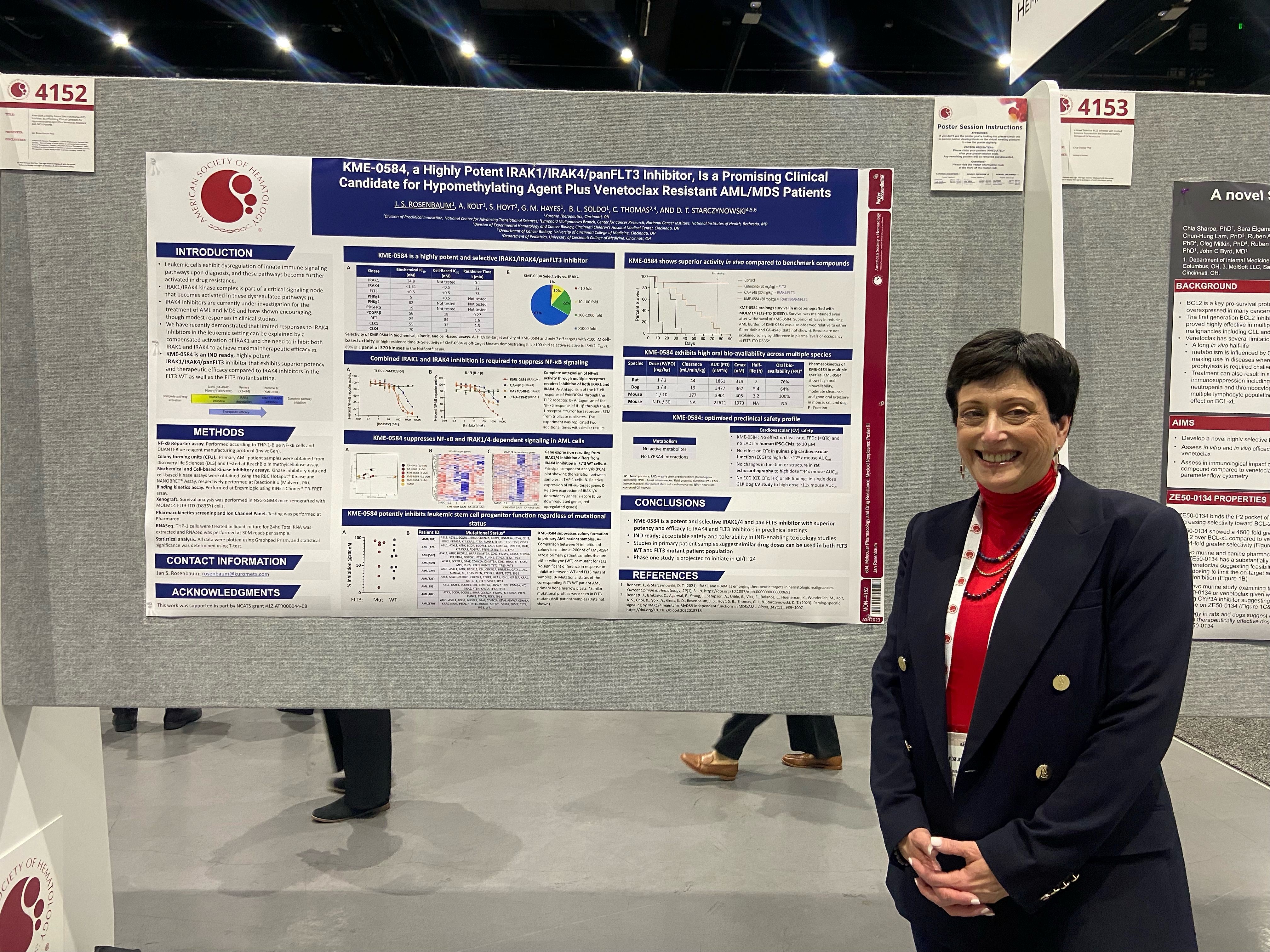

Rosenbaum founded Kurome Therapeutics in 2020, a startup focused on developing new therapies to stop the growth of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells. The disease, which invades the precursors to white blood cells in bone marrow, progresses quickly and is often fatal. According to the American Cancer Society, half of AML patients die every year.

In many of these patients, the cancer cells have figured out how to evade the body’s immune defenses. Rosenbaum’s work with Kurome focuses on overcoming this resistance. In healthy people, certain proteins carefully control how and when cells grow and divide. But in AML patients, the immune system is dysregulated, and cancer cells have learned how to hijack a particular immune signaling pathway in bone marrow, allowing the AML cells to proliferate unchecked as immature cells - blocked from becoming fully functional blood cells. Chemotherapy drugs often inhibit cancer cell growth, but these cells with hijacked proteins can evolve to resist the drugs.

“In AML, everybody becomes resistant,” she says. “But we’re learning more and more about the mechanisms of resistance.”

Kurome Therapeutics is working to identify and harness inhibitors that can rein in these mutant proteins, robbing cancer cells of their chemotherapy defenses. Rosenbaum, who served as Kurome's chief executive officer and chief scientific officer, left in May 2025 after a merger — but continues work with the company as a consultant.

The reduced workload turned out to be good timing. Rosenbaum was diagnosed in 2024 with multiple myeloma, a different type of blood cancer that develops in plasma cells. Her experience as a patient has deepened her empathy for patients participating in clinical trials, she says. After undergoing a biopsy herself, she now understands that while having more data from bone marrow biopsies would be ideal, it isn’t realistic. “Now I know how painful it is, and why you can’t do a lot of bone marrow biopsies,” she says, adding that she’s since learned that biopsies become less painful as the cancer retreats. “I kind of worked the patient experience into my thinking.”

Rosenbaum says her cancer — far more treatable than AML — was caught early and that she is responding well to treatment.

Her deep knowledge of cancer and the drugs used to treat it has also come in handy during discussions with her oncologist, she says. For example, she is working with her oncologist to determine what to test for in her next biopsy to see if she may need a stem cell transplant.

“I’m excited to learn what my biopsy will tell me at the end of treatment,” she says. “I’ve been able to use my knowledge from working in blood cancer to influence my own treatment.”

Rosenbaum, who holds a PhD in pharmaceutical chemistry, credits her time at UAlbany for putting her on the right career path. “I was deciding whether I should be a biology major or a chemistry major, and the head of the chemistry department said, 'Well, if you want to be a pharmacologist, you really should learn about drugs from a chemistry perspective and then pick up the biology on the side, because quite frankly biology is easier to learn than chemistry',” she recalls. “And he was very right. I left UAlbany with a very strong chemistry and biochemistry background.”

After earning her PhD at the University of California, San Francisco, she spent 23 years as a scientist at Procter & Gamble, but her entrepreneurial spirit eventually led her to strike out on her own, she says. At P&G, “I always knew I was a square peg in a round hole,” she says. “I was always collaborating with university professors and biotech companies. So I was entrepreneurial in a corporate culture, and I could see things years ahead of where the science was going.”

As a consultant, Rosenbaum continues to help lead pharmaceutical science into the future. In addition to her continued work with Kurome, she works with the Harrington Discovery Institute at University Hospitals in Cleveland to help other disease experts begin startups. Rosenbaum also teaches a drug discovery course she created at the University of Cincinnati Medical School.

“I’m working maybe half the time I was working before,” she says. “Everyone says relax, but relax isn’t in my vocabulary.”

UAlbany Magazine welcomes your comments and we encourage a respectful and on-topic dialogue. Comments that violate our guidelines will be removed.